On July 6th, 2018, the United States declared war on China. This war, however, is not being fought with bombs and guns or by millions of soldiers, but is being fought with tariffs. Trump and Chinese President Xi are engaged in a full-on trade war, and neither side is showing signs of concession.

Trump has never been a big fan of the way Americans have traded with the Chinese. He says that China is profiting too much from U.S farmers without returning the favor.

At the root of Trump’s decision back in early July to tax $34 billion worth of Chinese imports lies his belief that too much manufacturing abroad is hurting domestic industrial efforts. This protectionist philosophy is highly debated by economists and is complicated as it results in both negative and positive effects throughout the economy.

Trump’s policies are not popular with other countries that rely on a stable U.S trade relationship to meet their importing schedule. Engaging in tit-for-tat trade disputes may seem like it will yield results, but in the long-term, it damages crucial relationships that could hurt America’s biggest industries. One big American industry may take a permanent hit—soybeans.

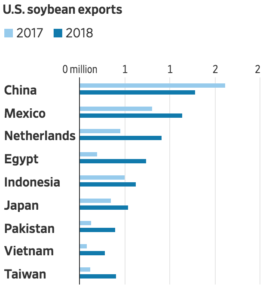

The United States’ biggest export is food, beverage, and feed according to a U.S Commerce report in 2017. Soybeans make up the largest part of that industry, and 60% of them were exported to China last year.

As demonstrated by a case study of the soybean market, the economic impact of tariffs on U.S. exports and a protectionist trade policy may damage the Chinese economy in the short term, but will eventually just push China to find alternative ways to avoid importing such high amounts of this product from America.

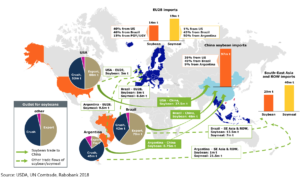

China does receive most of its soybeans from the United States, but it also gets them from Brazil. South America may be Xi’s best option if Trump doesn’t step down.

Though Brazil consistently runs out of soybeans at the end of each cycle, it could likely ramp up production efforts if need be. In the last 20 years, the country has increased its soybean production by 266%, whereas the United States’ production has only increased by 63%. However, production costs for Brazilian farmers may end up being too high to keep up with Chinese demand.

Another option for China is for investors to buy and develop land to produce soybeans in Brazil or another country, which would take a few years to fully implement. Then again, if this is a viable option in the long term, it could take away China’s need to rely on American soybean farmers.

President Xi’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is also a key player in reducing reliance on U.S agriculture throughout this trade war. The Initiative is an effort to connect Asia, Africa, and Europe for mutually beneficial economic opportunities. China wants a “belt” of overland corridors and a “road” of shipping lanes between 71 countries. That means the BRI streamlines trade between half of the world’s population and a fourth of the global GDP.

The BRI brings an increased level of economic interaction to China, making it that much easier to locate untapped areas equipped to produce soybeans other than the United States.

If China resorts to any of these options, U.S soybean farmers are going to take a long-term hit. While America can refocus its efforts to shipping out the product to other countries, if China manages to get Brazil to ramp up production levels or invests in agricultural land in other countries, it would lower the need for U.S trade partners to exclusively import soybeans from America.

China is now taking short term measures to deal with Trump’s tariffs. The China Feed Industry Association proposed in September to ration out soybean feed to pigs.

Furthermore, the Xi administration is maintaining a positive attitude by looking to increase domestic soybean production.

“Unilateralism and trade protectionism are rising, forcing us to adopt a self-reliant approach. This is not a bad thing,” Xi said in September.

The Vice Agriculture Minister Han Jun also warned that Trump is playing with fire.

“Many countries have the willingness and they totally have the capacity to take over the market share the U.S. is enjoying in China. If other countries become reliable suppliers for China, it will be very difficult for the U.S. to regain the market,” Han Jun told the Xinhua news agency in August.

Soybean producers in China are already benefiting from the conflict. Yang Guiyin, the sales manager of an agricultural company in the Heilongjiang Province, said that soybean profits are on the rise.

“Our farmers really hope that China will import less soybeans so that domestic soybean production and soybean-related businesses will flourish,” Guiyin told NBC News in July.

The Chinese Government is pushing its domestic agenda even further as it aims to add $1.6 million acres of land to its existing soybean production. It is also subsidizing $190 to $320 per acre instead of the previous $150.

On the other side of the war, the U.S is not taking a visibly huge hit just yet. Soybean producers have been able to maximize productivity this last quarter by exporting to other countries other than China. The profit margins on the products are still diminishing, however.

Some experts believe this will not last.

“I view this as being a surge that will not persist, but it’s huge,” Ian Shepherdson, chief economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, told the Wall Street Journal in July. “If you’re doing lots [of exports] in absolute terms at a time when normally you wouldn’t be doing very many, then the seasonals will be very favorable.”

Looking ahead, the future of U.S soybean farmers will be determined by conversation between Trump and Xi. The world leaders have planned to meet on several occasions, but due to rising tensions, have not been ready to negotiate quite yet. The White House decided recently to move forward with conversation. Trump and Xi are planning to discuss the escalating situation at the Group of 20 leaders’ summit in Buenos Aires at the end of November.

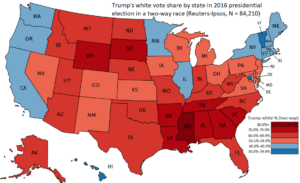

For the Trump administration, the pressure is on. President Xi purposely targeted the soybean industry because the farmers primarily reside in states that elected Trump to office. China is looking to hit his weak spots. If Trump’s support system loses faith, it could have detrimental effects for republicans come November’s elections.

Iowa, Minnesota, Nebraska, North Dakota, and Indiana are all major soybean producing states and all voted for Trump in 2016.

In any trade war, just like in real wars, people are hurt. Trump stands by his belief that the United States will beat China, but if Xi continues to match Trump’s level of tariffs, it could get very ugly. Americans have no choice but to wait and see if Trump is correct in tweeting that “we win big.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.