“I’m afraid there is no money.”

Probably not among the first things you want to hear less than 24 hours after being appointed by the Prime Minister himself to Her Majesty’s Treasury, is it?

But, this was what British Liberal Democrat politician David Laws was faced with on the morning of 13 May, 2010, his second day as Chief Secretary to the Treasury. In the letter Laws’ predecessor, Labour politician Liam Byrne, left for the new Chief Secretary, he wrote: “Dear Chief Secretary, I’m afraid there is no money. Kind regards – and good luck! Liam.” Although meant as nothing more than a jest, the letter ended up having a real impact on British politics. The Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government, well, mostly the Conservatives, used it as a proof of Labour’s previous economic failure under Gordon Brown throughout their time in government, and during the 2015 election. Just how bad was the economic mess that the coalition government had to deal with, and how did it impact British politics as a whole? Let me try to explain.

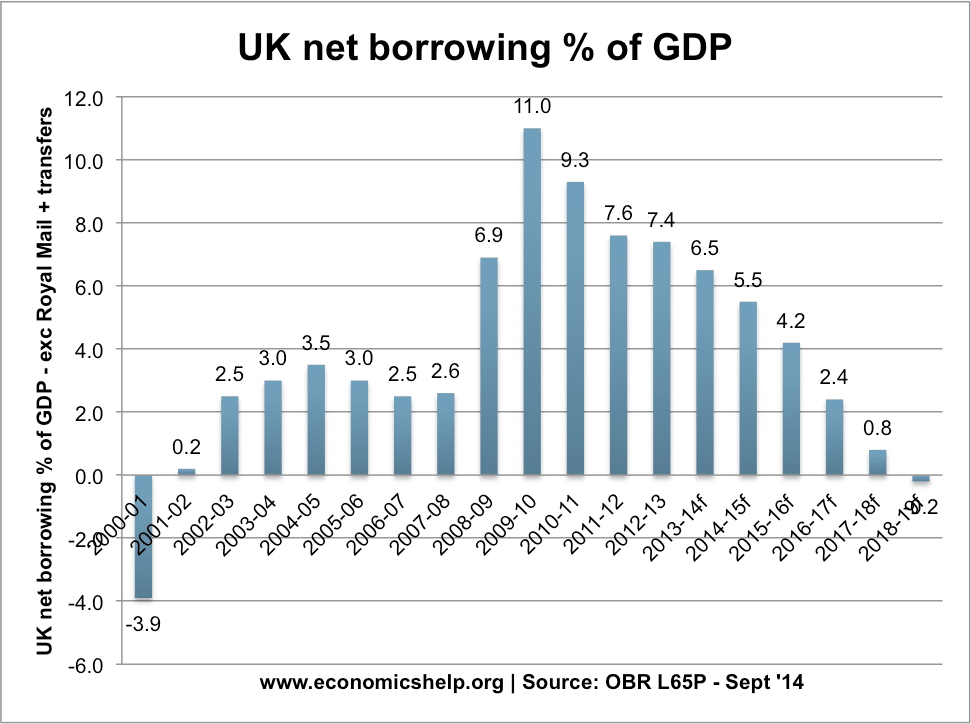

Since his premiership was, unfortunately, met with the global recession in 2008, when the then Prime Minister, Gordon Brown, called the general election in April 2010, the most scrutinized part of his legacy was a peacetime record-high deficit of £157 billion. As shown in the graph below, the United Kingdom borrowing in proportion to GDP shot up over 300% between the years 2008 and 2010. Admittedly, the global recession, like the name suggests, hit more than just the United Kingdom, and the Gordon Brown-led Labour party was hardly the main cause of it. Still, in the 18 months after the recession, the Brown ministry had no effective solution to it aside from more borrowing, and, as a result, the economy showed no signs of recovery. The failing economy was most likely what prompted Byrne’s joke. Unsurprisingly, Brown, the Prime Minister, lost him his credibility as an economic mastermind that he had built up over the past decade by producing and maintaining a strong and stable economy as the Chancellor.

In retrospect, the “no money” problem had been more than just an economic mishap for the United Kingdom. The aforementioned political, as well as economic impact, is turning out to be more profound than people had foreseen. In spite of Labour’s poor performance in the 2010 General Election, the Conservative party, though the biggest party, failed to win a majority in the parliament. Partly thanks to the extremely rocky economic state of the United Kingdom, Nick Clegg, leader of the third biggest party, the Liberal Democrats, put the interest of the United Kingdom above his party interests, and went into a full coalition with the Conservatives, so that the U.K. would not be stuck with either no government, or an unstable minority government. As most junior parties in the history of coalition governments worldwide, his party was diminished in the next general election, losing 49 of its 57 members for parliament. As they did with the letter, the Conservatives took advantage, and formed a majority government in 2015. Having promised a referendum on the EU, the Conservatives delivered it the next year, and led to the Brexit fiasco that we know of today.

As we can tell from the graph above, after the coalition government took over, slowly but surely, Britain’s debt problem healed. What is a lot harder to figure out is Brexit, which one could argue was, on some level, a byproduct of the economic mess that Labour had left. In an alternate universe, where Labour had proven slightly more competent in solving the recession, the Conservatives would have been less successful in the General Election, and probably would not have been able to deliver the EU referendum. Who would have guessed? Having “no money” could eventually be more harmful to a nation than just having no money.