Last week, the Turkish lira tumbled to an all time low post-2008, losing a third of its value and is, at present, around six lira to the US dollar. The ripples were felt in several emerging markets. In Argentina, for instance, as the peso slumped to a record low, the nation’s central bank raised its interest rate to a staggering 45%. The currencies of South Africa, Brazil and Mexico were also affected.

In an article in Forbes, Jesse Colombo wrote that since 2002,“Turkey’s economy nearly quadrupled in size on the back of an epic boom in consumption and construction that led to the building of countless malls, skyscrapers, and ambitious infrastructure projects. Like many emerging economies in the past decade, Turkey’s economy continued to grow virtually unabated through the Global Financial Crisis, while most Western economies stagnated.”

Taking advantage of the low interest rates after the global recession of 2008, Turkish banks and firms drew on massive foreign loans to fund a relentless drive towards economic growth. Turkey’s real GDP grew by more than 34% in the last five years – only slightly less than China and India.

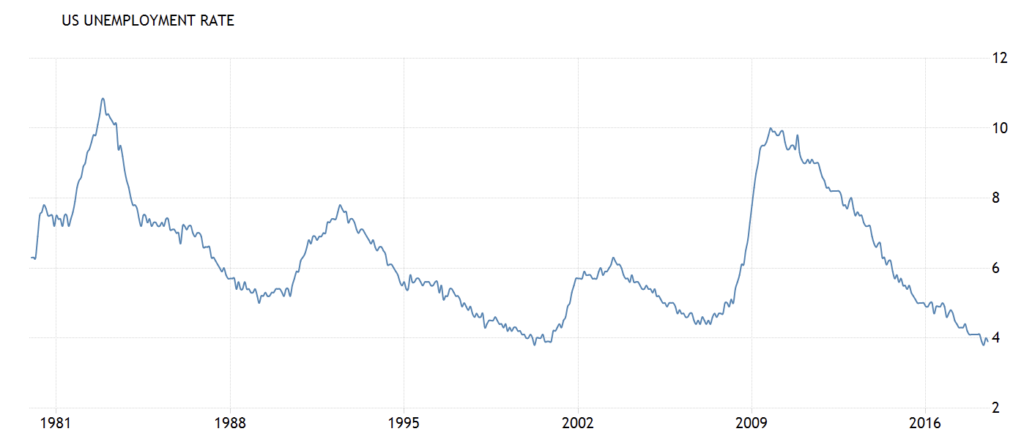

Things were looking up for quite some time: the labor force participation rate steadily increased, youth unemployment rate dropped, and the inflation rate was mostly steady. But there had always been indicators of the impending collapse that would burst the bubble.

Turkey’s growth has been so dependent on financing from foreign investors that the nation’s total gross external debt reached around $466657 million in the first quarter of this year. Turkish banks had borrowed money at low rates from European and American banks right after the recession so that they could, in turn, loan the money out to Turkish companies. But as the value of the lira plummets, it seems more likely that the companies would be unable to pay back the loans, therefore also affecting Europe and the United States.

While the country’s inflation rate had more-or-less steadied itself between 2010 to 2016, it started spiraling upwards from the middle of 2016 and sky-rocketed in the past two months. The Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey was prevented from making the necessary interest rate adjustments to fix the crisis.

President Erdoğan is a believer of the idea that interest-based banking is “prohibited by Islam” and has also claimed that increasing the rate of interest is “treason”. Throughout his tenure as president, he has gradually stripped power and independence of financial institutions. After acquiring sweeping executive powers after his re-election in June, he resisted the bank’s calls to increase the interest rate. Perhaps in an effort to assert greater control of his country’s economy, Erdoğan appointed Berat Albayrak, his son-in-law to the office of Treasure and Finance Minister last month.

What can Turkey’s implosion teach other countries?

While the collapse of the Turkish economy would obviously affect the countries that invested the most in it, the indicators that should have ideally served as warnings of an impending collapse, can also teach something to other emerging markets. Several developing countries weathered the global recession and, like Turkey, used foreign investments to fund staggering levels of growth. Two examples are India and South Africa.

While the India’s external debt has steadily increased in the last ten years, it has so far managed tokeep inflation under controlwhile at the same time reporting high GDP growth rates. While India dealt with the global recession much better than most other states, in recent months, the Indian currency has taken a hit, perhaps indicating that the world’s second most populous country is walking an economic tight-rope.

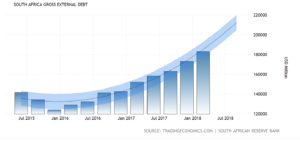

South Africa on the other hand is on the exact same trajectory as Turkey. Its external debt has rapidly risen and while the inflation rate was under control for some time, it has shown a steady increase and is set to increase again. The labor force participation rate of the country has also been steadily falling over the last few months.

How politics burst the Turkish bubble

Besides purely financial factors, the rule of law too has an effect on a nation’s economy. Among other things, politics was also responsible in causing a decline in Turkish fortunes. Local businesses got caught up in the government crackdown of dissenters post the failed coup d’étata couple of years back. It has often reached ludicrous levels. According to a report by NPR, for instance, a certain brand of carpet stopped selling because the factory that manufactures it had been raided by the police for alleged links toFethullah Gülen, the United States-based cleric whom President Erdoğan accuses of orchestrating the coup.

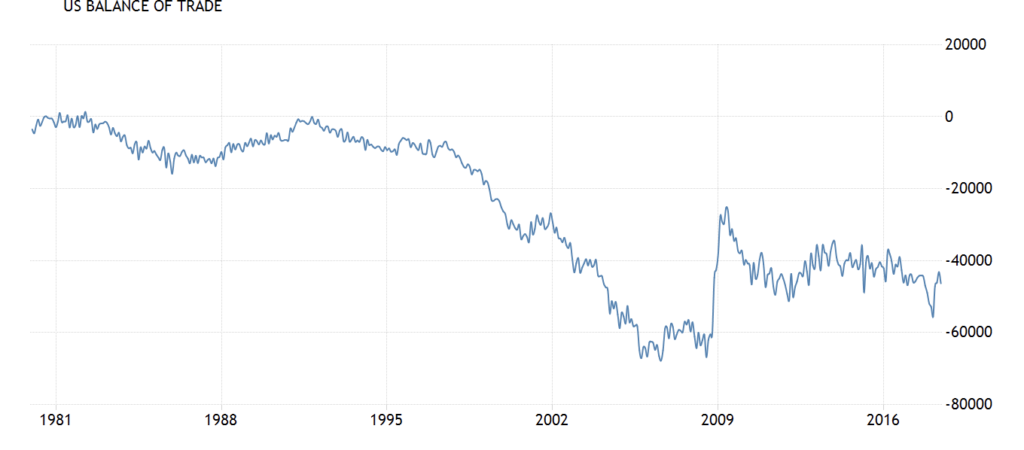

Internationally, the relationship between the United States, a major investor, and Turkey have recently worsened over a variety of issues ranging from Turkey’s continued detention of Andrew Brunson, an American pastor allegedly linked with the coup, the nation’s handling of the Syrian crisis, and its cozying up to Russia. The financial crisis was in-part accelerated by President Trump’s decision to double steel and aluminum tariffs on Turkey.

While the crisis in Turkey could affect the United States, Europe, and some emerging markets of developing countries, it could further destabilize the economies of neighboring Iraq and Syria, further destabilizing a region already torn apart by war.