First came the taxi hailing and riding-sharing apps Didi and Uber, then there was the lodging app Airbnb. China has been fully embracing the concept of “sharing economy” in recent years, and the next big trend is here: dockless bike-share. Founded in 2014, ofo has now become the leading bike-share company in China and is valued at $2 billion. Today, ofo has 200 million users and is operating in more than 100 cities globally. While it seems like ofo fits every definition of a successful internet start-up, many people are questioning whether this rare unicorn is in fact a giant bubble waiting to burst.

It all started when 5 college students in the cycling club of Peking University, one of the most prestigious colleges in China, decided to create a student project together involving bikes. Dai Wei, the 24 year old CEO and co-founder of ofo first came up with the now household name because the letters are shaped like a bicycle. At the beginning stages, ofo was only operating on the campus of Peking University. Students who offer their own bikes for ofo’s bike-share program will gain access to use all the other ofo bikes around campus with a small charge, including the initial 200 bikes Dai bought. What is different about ofo is, these bikes do not need to be parked at specific bike stations. Users can look for bikes near them, and park the bikes at their convenience at the end of their trip. In September 2015, 1,000 more ofo bikes were brought to the Peking University campus. In a month, the amount of orders ofo received daily grew from less than 200 to over 4,000.

After its successful launch in Peking University, ofo quickly expanded to five more prestigious universities around Beijing. However, the team soon realized that they cannot rely on the students to share their own bikes to quickly grow their user base. Rather, the company learned that it needed to buy more bikes because easy access to the bikes is what attracts more people to use their app. From then, ofo has been through many rounds of venture funding, capturing more capital each round. Data from Crunchbase shows that ofo received 10 million RMB ($1.5 million) in series A funding in January 2016. In October, the start-up was able to raise $130 million in a series C round. In the latest D and E rounds, ofo raised $450 million and $700 million led by DST and Chinese tech giant Alibaba, respectively. With all this capital in hand, ofo has been doing one thing—expand. In 2016, ofo owned 85,000 bikes; this year, that number has gone up to 10 million.

Exactly what kind of business model attracted so much capital? Today ofo operates by charging users 0.5 to 1RMB ($0.07 to $0.15) an hour to use their bikes in China. Their pricing overseas is usually higher, at around $0.5 to $1 an hour. Users have to download an app on their smartphone, pay a 199RMB ($30) security deposit, and scan a QR code on the bike to unlock and use it. This is a big shift from when ofo operated solely on college campuses, which are better regulated environments with clear demand. Also, because ofo collected student owned bikes, the pricing was likely profitable. Today’s ofo effectively operates as a bike renting company, even though it is still being marketed as a “bike-share” company. Ofo is fundamentally different from ride-sharing apps like Uber or Didi because it does not provide a two-sided platform connecting riders and drivers. There is no network effect, namely, the value of ofo’s service does not increases with the number of users on the platform. Moreover, unlike Airbnb, there is no significant asset-sharing going on with ofo. It is not part of the sharing economy where companies connect users with assets owned by someone else that are underutilized. Airbnb does not own a singlepiece of property but uses other people’s “spare rooms”, whereas ofo directly owns all the bikes its users are paying to use. “What they’ve got is a very interesting technology, but a basic business model that makes no sense,” says Paul Gillis, an accounting professor at Peking University.

Is the new ofo model actually profitable? It seems like no one has a definitive answer to that question. Michelle Chen, COO of ofo claimed during an interview with Financial Times China that the company has gained profit in a few cities, but refuses to reveal any details about the profit margin or name the cities. In fact, many believe that the current business model of ofo may never profit. “Across the board, what we are seeing is non-economic behavior and a race for scale that is fueled by hype and enabled by easy access to money”, says Jeffrey Towson, a private-equity investor and a professor of investment at Peking University. Towson believes that the biggest issue with ofo is that its pricing is “almost certainly unprofitable”. Ofo bicycles are reported to cost 500 RMB ($75) to manufacture. According to the company’s official website, there are currently around 10 million bikes in use and 25 million rides registered per day. Assuming each rider spends 1 RMB on each trip, it would take about 200 days to recoup the production expense of a bike. Although this seems like a rather promising calculation, with high expense for maintenance, as well as theft and vandalism charges, the odds of breaking even drops immensely.

Ofo needs to hire numerous maintenance teams to move the illegally parked bikes, and to redistribute bikes in areas with high demand because there are many complaints of the bikes blocking the streets and pedestrian walkway. The maintenance teams are also responsible for tracking down bikes that are vandalized, stolen or reported broken and unusable. Videos of people throwing ofo bikes in to canals have gone viral on the internet, and there are also reports of the QR codes being intentionally defaced so that users are not able to scan and unlock the bike. Unlike Uber and Airbnb, where most of the tasks involved with purchasing and maintenance are outsourced to users (drivers, hosts and guests), ofo has to take these losses and put a lot of money and effort into the maintenance of bikes. Essentially, the very factors that make ofo’s bike-share services so convenient—low prices and ease-of-use, have resulted in razor-thin margins and widespread customer negligence, and are making it difficult for it to stay afloat.

A mechanic from Ofo stands amongst damaged bicycles needing repair in Beijing. Photograph: Kevin Frayer/Getty Images

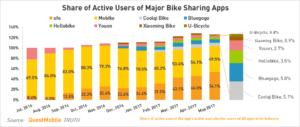

Despite the still lingering questions about the ultimate profitability of ofo’s business model, the company continues to carpet bomb China with hundreds of thousands of bikes. The main reason why ofo is taking this strategy is that it is fighting for the market share. Even though ofo is the first dockless bike-share company, many copy cats soon entered the competition and are putting their own colorful bikes on the streets of China. In 2016, 30 different bike-share companies were operating around China, scrambling for investments and users. Mobike, ofo’s largest competitor backed by Tencent, was able to surpass ofo with a 69.5% share of active users of bike-share apps. With the support of more capital, ofo stroke back this year with more bikes and promotions to attract users and regained its lead in the market. However, it appears that this fight for market share between different bike-share companies will not end soon. Michell Chen, COO of ofo claimed that the company’s goal for next year is to continue its expansion by putting more of its bikes in more cities. Mobike and smaller competitors including Youon and Mingbike are also planning on further expansion. This creates continued competitive pressure on already likely razor-thin, if not negative, operating margins.

Under ofo’s current business model, revenue depends on getting rides, and getting rides depends on making sure bikes easily accessible wherever you are. One way to ensure that a potential rider always has a bike nearby is to put dozens of bikes on every street corner, but that has led to chaos and oversupply. In August, Shanghai’s municipal transportation bureau sent a notice to a number of bike-share companies demanding they refrain from adding more new bikes on the streets. The notice also asked these companies to relocate bikes parked and scattered carelessly across the city. According to Quartz, Ofo said it was addressing the problem in Shanghai in an interview with China’s Hubei Television in August.“This month Ofo has dispatched 80 extra carts [to relocate bikes], and we have a total of 2,500 operations staff working on cleanup and repairs,” said Hu Yun, chief of Ofo’s operations in Shanghai. “We are proactively cooperating with the government’s calls to clean up the city.” By the end of November, the city has already cleared out 500,000 excessive bikes (link in Chinese) put on the streets. The government also called for the comapnies to register the 1.7 million sharing bikes (link in Chinese) in the city. Similarily, authorities in Beijing, Shenzhen, Guangzhou, Wuhan, and many other cities also put the brake on adding more shared bikes to the streets. With five operators, including Ofo and Mobike, expanding rapidly since in the city at the end of last year, Wuhan’s urban districts now has 700,000 shared bikes (link in Chinese), far exceeding the city’s carrying capacity of 400,000. The government stepping in to prevent the companies from adding new bikes on the streets is no small hindrance for the industry’s core business model. Ofo now needs to spend even more resources on maintenance under the government’s tight scrutiny, and needs to figure out new ways to expand their business.

Thousands of share bikes laid to rest in the south-eastern Chinese city of Xiamen. Photograph: Chen Zixiang for the Guardian

In the past six months, six different bike-share companies has went belly up (link in Chinese), and over 1 billion RMB ($151 million) of users’ security deposit has been lost. In July, some users of Mingbike claimed that they were having problem getting their security deposit back, causing many users to request their money back from the company. Employees of the company claimed that they still owe 250,000 users a total of 50 million RMB ($7.55 million). In August, Dingding was branded an “abnormal enterprise” by the authorities due to illegal fundraising and cash flow problem, and was not able to return the security deposit to over 10,000 users. In September, when many users of Bluegogo bike found that their refund of security deposit was overdue, Chinese social media erupted in complaints about the company. With more than seven million bikes, Bluegogo was the third largest bike-share company in China and had expanded their business into Sydney and San Francisco. Nevertheless, the company failed last month in what analysts say is the sign the country’s bike-share bubble may be bursting, leaving thousands of users without their deposit back.

Over the past two years, China’s bike-share companies have grown in an astonishing speed and have taken over the streets with colorful bikes. However, it is clear that there has been far too many players backed by far too much venture funding chasing far too little profit in the sector. Moving forward, even well-managed and well-funded ventures like ofo will face an uphill climb. Many peole predict that ofo will eventually have to merge with its biggest competitor, Mobike, in order to stop burning money and focus on turning profit. Earlier this year, CEOs of both companies have made it clear that they would not consider a merger. However, since the landscape in China’s bike rental industry has been settled with ofo and Mobike accounting for 95% share of the market, the attitudes of investors behind these companies are growing more favorable towards a merger to end the costly competitive battle, according to Bloomberg. Will the two companies join forces to become a single leader in the industry? Will ofo be able to achieve its goal to turn a profit in 2018 under its current business model? How will ofo manage its many branches overseas and adhere to local policies? For now, the future of the company remains unclear.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.