Ninety-seven percent of the world’s global water supply is salt water and of the 3% remaining, only 1% is available for human consumption. Economics is all about scarcity, and like any other scarce resoruce, water and water shortages can create investment opportunities.

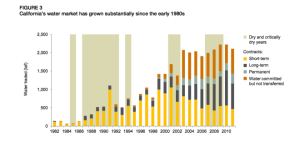

The introduction of a water market in the United States – specifically in the western region of the nation, where demand is increasingly high and supply (conversely) is shrinking – could potentially aid water crises in states like California, which has a history of shortages and droughts.

In countries like Australia and Chile, where water-trading markets have already been implemented, water usage has decreased dramatically, while simultaneously curbing waste. There — of course – have been issues raised among critics, who view the trading of water rights as a privatization of water and an attack on the commons, whereby only those who can afford and are willing to pay for the commodity are given access to a life– supporting resource. These concerns can be addressed with proper policy making that will guarantee a minimum supply to households.

Australia has the largest system of water trade in the world. The development of the nation’s water-trade market came about as a response to severe drought and water shortages. The country introduced its market in 1983 as a way of reallocating the resource to sectors that demonstrated the most need and productive use of the resource. Citizens are given rights to a share of the water that is available in the Murray-Darling basin, located in South Australia, annually. Instead of basing allocations off of a specific quantity, the shares system reflects appropriate amounts of water actually available in the Murray-Darling during a given year. Australia’s Market is highly regulated and operates on a cap-and-trade system that sets a limit on the amount of permits given to water extractors and irrigators and creates a market for the resource. The first “pilot interstate water trading project” launched in 1998 and made the trade of permanent water entitlements possible. Today, a growing number of temporary, usually annual, trade allocations take place through the use of electronic exchanges and third parties, such as lawayers and brokers. Cap-and-trade is commonly used in environmentally minded economic policies as a mechanism for controlling the amount of impact on the environment. The European Union attempted an approach to controlling greenhouse gas emission via a cap-and-trade policy, but the program is generally regarded as a failure due to an over issuing of permits that created an ineffective system where there was no need to buy or sell the emission permits (Sky News).

The cap in Australia’s case is the amount of water available for use. Water is distributed via water rights administered by the country’s governing body. For Australia, the system resulted in a reduction of waste in overall water usage because it accounts of yearly rainfall and shortages. In years where the country faced particularly dry weather conditions or drought, the price of water rose but the number of trades off-set the rise in price: “People used the market to move water where it was needed – and valued – the most. Water-intensive crops such as cotton and rice were temporarily phased out as the water needed to grow them became more valuable than the crops themselves,” (Lustgarten, The Atlantic). The average price of temporary water rights has for the most part flucuated between $10 and $85 a megaliter (Curran, Forbes).

The water market has essentially allowed the users themselves to make decisions – rather than political bodies — about water usage. In doing so, Australia’s use of water supply has created financial incentive for smarter use: “Farmers in an irrigation district that had porous dirt ditches, for instance, began to line them with concrete, saving millions of dollars’ worth of water that would have otherwise seeped into the earth,” (Lustgarten, The Atlantic).

Similar ways of reducing water usage and cutting waste could be utilized in agricultural regions of states like California. In fact, modern technology has been developed to cut water use by up to 50 percent, though farmers are not motivated to adopt these technologies because of the current water laws set in place. California’s state water law was established in the 19th century during the height of the gold rush, “based on the old miners’ code: first in time, first in right,” (Coy, Bloomberg Businessweek). This prior-‘appropriate water rights doctrine’ – now over 160-years-old – gives first dibs to the first person who takes a quantity of water from a source for “beneficial use.” In doing so, it gives that person the right to continued use of that quantity from the source, for his expressed purpose. There is essentially a use-it or lose-it mentality that has de-incentivized users to conserve.

The current market California operates on has had some success, but because of ambigouty in the out-of-date laws, it is hard for sellers to prove the water they are selling is legally there’s, which have left many potential buyers and sellers ambivalent about entering into trades. If water policies were modernized to reflect the current economic priorities via measures like the implementation of a water market farmers may feel more encouraged to sell off their surplus, rather than let it go to waste.

An additional problem raised by California’s agricultural sector is the economic out-put ratio of water consumption. Farms in the state consume 80% of water while only generating 2% of gross domestic product for the economy. While the agricultural sector is intertwined with other economic categories, such as transportation and warehousing and finance and insurance, which — to a degree –rely on the thousands of farms that utilize their services, there can simply be no arguing the disparity in amount of water usage in the agricultural sector (Ross, Los Angeles Times).

Water markets could check the use of water, shifting agricultural production toward higher-value crops and away from low-value crops that often demand higher amounts of water. Like in the case of Australia, rather than displace farmers by limiting access to available water, the water market could lead to a behavior change in the agricultural sector, especially in areas plagued with drought, by encouraging a switch to crops with higher-value and/or lower demand for water. For example, decreasing the amount of alfalfa crops, which require a large sum of water and can be produced in states with richer supply, while increasing the amount of vineyards and tomato crops, could improve the gross domestic product of the agricultural sector.

Clarifying water rights is a necessary step towards solving California’s drought crisis. Laws that are concrete and clearly defined will make trading water a whole lot easier because, in order to trade, stakeholders must first understand what it is they are selling. A state law passed in 2014 aimed at regulating and monitoring the pumping of groundwater in the state is indicative of steps being taken by the government to enact a regulatory body for the resource. However, these laws will not take full effect until 2040 (Coy, Bloomberg Businessweek).

In the meantime, improving the information about water availability and calculating how much can be utilized without harming the environment would paint a clearer picture of how the resource should be managed. Additionally, building a central regulatory system and repository of information could aid in the establishment of appropriate water valuation (Hanak, Public Policy Institute of California).

The state has already experiment with a cap-and-trade program to cut greenhouse emissions. The program, which began in 2014, has efficitively reduced overall pollution and is on track to achieve 1990 levels by 2020, a more than 15% reduction from 2015 (Hiltzik, The Los Angeles Times).

California has one of the most extensive water-supply systems in the world and the largest out of any states. The infrastructure the state currently has is entirely sufficient for storage and supply of water to farms, industries and growing cities, but conservation – as previously stated — has yet to be incentivized. The development of ground water aquifers for conservation would allow irrigators to store water in times of surplus, just like a savings account, thus softening the strain placed on the supply of the resource during dry spells (Manning, Reason).

SOURCES:

http://www.latimes.com/opinion/op-ed/la-oe-0602-ross-sumner-water-agriculture-20150601-story.html

http://www.waterfind.com.au/water-trading-explained/

http://fortune.com/2014/06/25/water-futures-markets/

http://www.ppic.org/main/publication_show.asp?i=1177

https://ww2.kqed.org/science/2014/09/17/what-to-know-about-californias-new-groundwater-law/

https://www.arb.ca.gov/fuels/lcfs/workgroups/lcfssustain/hanson.pdf

http://news.sky.com/story/water-trading-from-rainfall-to-cashflow-10348114

http://voxeu.org/article/price-precious-commodity-water-trading-australia

http://www.latimes.com/business/hiltzik/la-fi-hiltzik-captrade-20160728-snap-story.html

http://grist.org/food/california-has-a-real-water-market-but-its-not-exactly-liquid/

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.