It would be untrue to say that it is only recent that Latin America has gone through political turmoil. Countries like Chile, Colombia and Bolivia have been on the spotlight this year. Much of this discontentment sources from economic failure that has brewed for years. Politicians are very extremists with their economic policies going from promises of extreme capitalism or socialism. More recently, Evo Morales, former president of Bolivia resigned after thirteen years of presidency, but he calls his removal a coup. What lead to this moment?

Morales came to power in 2006 as a member of the left-wing Latin American group that included Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez, Ecuador’s Rafael Correa and Argentina’s Cristina Fernández de Kirchner (Washington Post) He was the last man standing, being the leader of the Movement for Socialism party throughout his whole presidency. Bolivia has changed dramatically since Morales started his presidency.

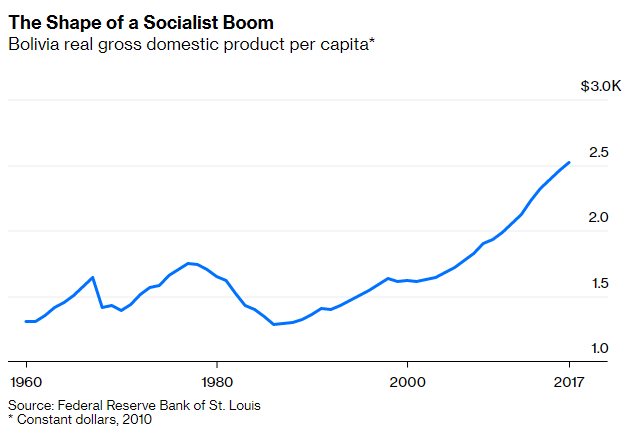

When Morales took oath, Bolivia was the poorest country in South America in 2006. Currently, Bolivia is still the poorest in some measures such as lowest alphabetization and income. But overall, Bolivians are healthier, wealthier and living longer than before. The GDP grew from $9 billion in 2005 to $36 billion in 2018 (COHA). It seems then, at least on paper, that socialism worked.

However, it was not traditional socialism that was taking place in Bolivia. It was, as Evo explained a different model, “The state as the head of investment, accompanied by the private sector — that is the model of socialism we have.” Morales redistributed income through various government programs, raised minimum wages substantially, and nationalized industries such as telecommunications, oil and electricity (Bloomberg). All while also working with the private industry.

To the outside world, Bolivia was doing great. By 2017, Bolivia was 42 percent richer than when Morales took office and poverty declined by 25 percent since he was elected (Bloomberg). So why there was general discontent? It had to do with his authoritarian tendencies and breaking presidential term limits. The 2009 Bolivian constitution prohibits more than two consecutive terms, and he had been allowed to serve three consecutive terms as President due to a 2013 ruling of the Supreme Tribunal of Justice, where Morales first term did not count towards the term limit because it took place prior to the ratification of the constitution (BBC)

There was a referendum held on 2016 that planned to eliminate term limits, the socialist party narrowly lost and the Supreme Court overruled the constitution, meaning that Morales could run again in 2019 (The Guardian). Bolivia, along with Nicaragua, is the only presidential democracy in the American continent with no limits on re-election. The lower and middle class continuously supported Morales in his quest to get reelected, whereas the upper class demanded for his third term to be the last.

A partial nationalization of Bolivia’s oil and gas helped create a middle class from scratch. Bolivia is Latin America’s fastest-growing economy, where 53% of its legislators are women and a fifth are under 30. However, Morales approval rating was damaged by allegations that he used his political influence to favor a Chinese construction firm in which his former girlfriend, Gabriela Zapata Montaño, held an important position (BBC). Morales denied the allegations and said he had nothing to hide.

As mentioned before, Morales partially nationalized its oil and gas. Previously, corporations paid 18% of their profits to the state, but Morales reversed this, so that 82% of profits went to the state and 18% to the companies. The oil companies threatened to take the case to the international courts or cease operating in Bolivia, but ultimately relented (COHA). Over ten years, Bolivia gained $31.5 billion from the nationalizations, compared to a mere $2.5 billion earned during the previous ten years.

In my first project, I explained how Chavez made certain choices that from a viewer standpoint were beneficial to the people. Same thing with Morales. One of the first things as a president was to relocate state-owned lands, and “expropriate” lands that the Ministry of Agriculture sought to be nonproductive by those who owned it. A consequence of this was the internal production of basic products by individuals and small farms to lower and rely even more on the oil and gas industry of the country.

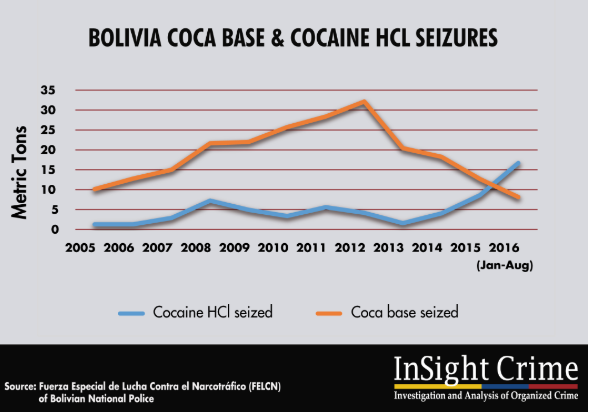

It is important to mention that Bolivia received a lot of help from Venezuela through monetary aid. With this aid, the country was able to finance betterment projects such as the industrialization of coca by building plants such as the one in Chulumani (Al Jazeera) the project was primarily funded through a $125,000 donation by the Venezuelan government. Coca in Bolivia is considered medicinal, the leaves are harvested and sold as tea. The problem with this is that coca is illegal in most countries, making extremely difficult for Bolivia to sell in the international market. After much lobbying, the UN finally decriminalized coca in 2013. The result was the increase of cocaine seizures (Insight Crime) Between January and mid-August 2016, the police’s antinarcotics unit registered 16.7 metric tons of cocaine, which was already nearly double the total figure for 2015, when 8.6 metric tons were intercepted. For the U.S and other countries, Evo Morales was as an accomplice of drug traffickers and systematic drug rings in South America.

Morales openly talked bad on the upper class, calling them “burgueses” just like Chavez did. This also meant that he presented very anti American sentiments on international conferences and to its people. There was a lot of resentment inculcated to the lower class, where this idea of “those rich kids don’t know our struggle” and that he, Evo Morales, would personally make sure that they wouldn’t struggle. This kind of propaganda was very popular during that time, especially with Chavez being alive. The gap between the lower and middle/upper class became bigger in the social sense more than the monetary.

There was one thing that both classes agreed on this past year, is that another term was starting to feel authoritarian. His party, Movement for Socialism, had been the majority party in all governmental agencies leaving little to no space for other member parties to be able to engage in the conversation. Something that is very important to mention is that most countries in South America have religion at the center of its politics, especially Catholicism. However, there has been an increase of Evangelism in the poorest communities and this was reflected in the most recent congress election. In Bolivia (and in the majority of the world), indigenous groups are often misrepresented and not heard. There are a total of 36 recognized indigenous people (Minority Rights) and even though three indigenous-specific universities had been established, which offered subsidized education there was an increase in racial tensions between indigenous, white and mestizo populations. To make things worse, part of the agrarian reform of relocation of land was in part to redistribute land to traditional communities and not individuals.

While the efforts to integrate the indigenous communities and provide them with education and access to the public system were highly anticipated, some communities did not integrate as well, furthering creating a cycle of poverty in these groups. Though the country operates in mainly extraction of natural gas, more and more indigenous groups felt as this was hypocritical and poor use of the community’s lands. This dissent was also felt when in 2010 Morales announced a 5% increase in minimum wage and The Bolivian Workers’ Central (COB), which was formed by a majority of leftist and indigenous individuals, felt this insufficient given the rising cost of living, calling a general strike. Eventually, the government relented and agreed to the wage rise (Reuters)

Morales changed Bolivia, growing its GDP and lowering the unemployment rate. However, what is the future of Bolivian economics? What would it look like?

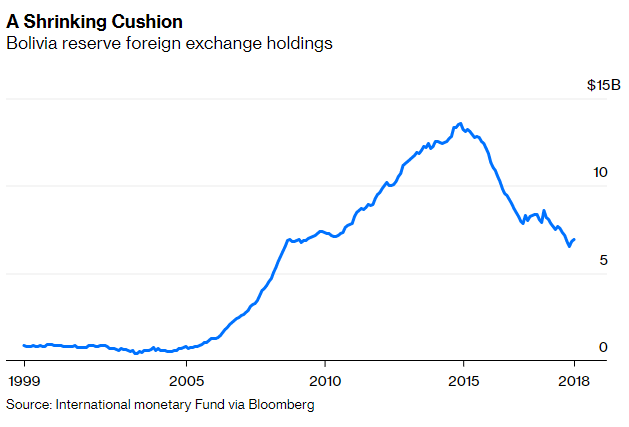

In Timothy Kehoe, Carlos Gustavo Machicado, and José Peres-Cajías “The Monetary and Fiscal History of Bolivia, 1960-2017” they explain that Bolivia’s success may not last forever (Bloomberg). The first thing they wrote about is how since 2008, Bolivia’s exchange rate has been effectively pegged against the U.S. dollar. A pegged exchange rate, also known as a fixed exchange rate, is a type of exchange rate in which a currency’s value is fixed against either the value of another country’s currency or another measure of value, such as gold (Investing Answers) So, what does this means for Bolivia? It means that if the country ever runs out of dollar assets, it won’t be able to stop the boliviano from depreciating, resulting in a very rapid crash in the currency’s value.

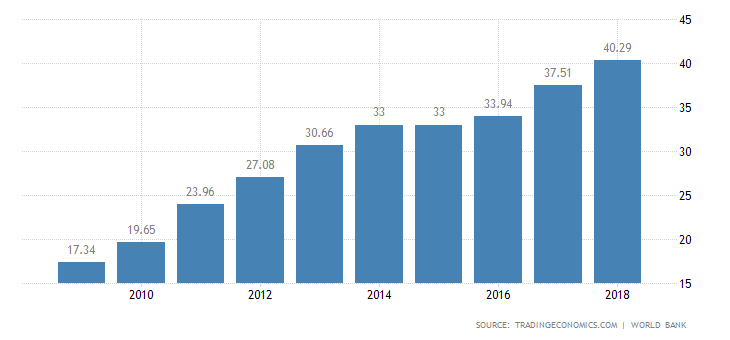

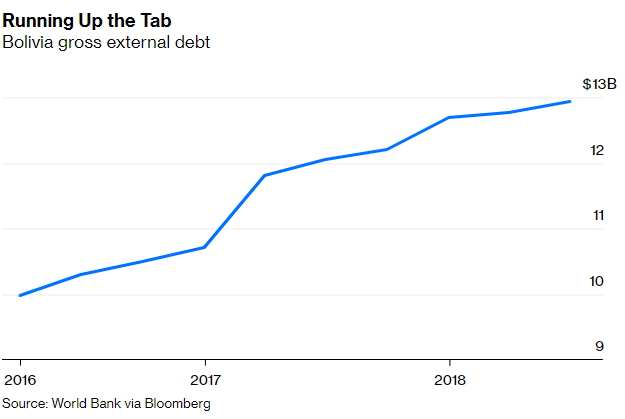

The other factor that they wrote about was Bolivia’s increasing external debt. The amount that Bolivia’s government owes in foreign currencies has approximately quintupled since 2007. The country’s total external debt has gone up by about 30 percent. What would make the government to run out of foreign exchange reserves? A commodity price drop. Lower global commodity prices are probably the reason that Bolivia has been running down its reserves since 2014, and we know that they rely on commodities for the majority of its exports.

It will be interesting to see what the future holds for Bolivia, hopefully good things will come.

Sources:

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-22605030

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-35628093

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evo_Morales#Economic_program

https://www.thenation.com/article/economics-socialism-bolivia-evo/