The American newspaper industry has used advertisements as its main source of revenue ever since the very first colonial publication, the Boston News-Letter, printed a real estate ad in 1704. Though this “newspaper” was only a half-sheet, single-spaced weekly journal, it p aved a business model that would be used over the next three centuries. Then, nearly three hundred years later, the wheels came off the wagon. It no longer made economic sense to pair editorial content and advertising together in a printed product in the age of ad networks and digital distribution. Paperboys found themselves unemployed and traditional reporting jobs dried up. The digital revolution’s effects are still playing out, but there seems to be a way for publishers to charge ahead—by focusing on differentiating content and by taking exclusive ownership of high-quality, specific data that is valuable to advertisers. Many papers have revised their business models to target younger, more internet-savvy audiences. After all, when an e-commerce pioneer like Jeff Bezos buys the Washington Post, it’s clear that journalism is merging into the virtual sphere. But the dust has not totally settled. The field may look like it is heading in certain direction now, but things are constantly changing. It’s important to remember that just a few decades ago, most people would have never guessed that physical newspapers would start to disappear.

Prior to the internet, publishers had the upper hand. They had limited space in their newspapers and advertisers were willing to pay for a section so that readers could see their product. Although not every reader fell under the demographic most likely to be interested in purchasing, advertisers could buy up as much space as possible and thus increase the likelihood of reaching people from that specific group. Technological advances, however, took out the element of scarcity—theoretically, anyone in the world could access the internet and read content that was once only accessible by purchasing a physical copy at a news stand. This made the price of a non-tailored advertisement close to none. Advertisers became much more interested in placing their ads on websites that attract their target demographic rather than buying as much ad space as possible and hoping that group sees it.

People who were only interested in reading one specific section did not have to buy the entire paper to access it—media was finally unbundled. It created the ability for businesses to choose to advertise in places where their target demographic frequents, making their strategy less reliant on volume and more reliant on consumer data and tailored audiences. If someone wants to read the latest updates in the fashion section, they do not need to buy the politics and sports section as well.

This kind of shift, however, has been seen before. Journalism is not the first industry to have been affected by the unbundling of media. When technology allowed people to purchase individual songs on handheld devices without buying the entire album first, the revenue landscape shifted. Suddenly, Apple and other streaming services had a slice of the revenue pie, and that pie was also shrinking. Overall recording revenue fell, and artists were getting the short end of the stick. Many songwriters, like Taylor Swift, fought back on social media. Taylor released a letter exposing Apple’s stingy licensing agreements. Artists who previously relied on selling music to make a profit are now more focused on merchandising and concert tickets.

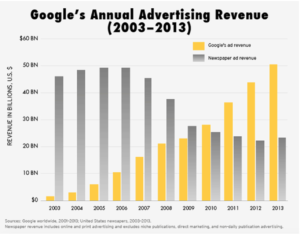

Similarly, the internet has ushered in an urgent need for newspapers to adapt and find ways to make money. For the journalism industry, the unbundling of media was a good thing for everyone involved except for the publisher. It led to a major power shift—advertisers now want to do business with networking and search engine companies instead of newspapers. Facebook and Google have a virtual duopoly on the digital advertising market, which grew 21% to $88 billion in 2017. The two companies accounted for 90% of that growth, and reason is simple: access to information. More than one billion people—who have likes, dislikes, friends, and interests—are active on Facebook. Google has a similar advantage as it processes more than 70% of the world’s search requests. When you search something on Google, the company finds out where you are and tracks what you’re searching, compiles that information, and sells it to potential advertisers. Advertisers were no longer willing to pay newspapers high amounts because it makes much more sense for them to pay Facebook and Google.

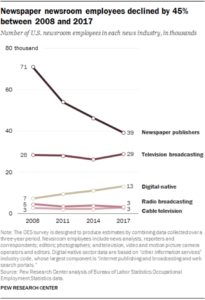

Unfortunately, rapid technological changes have a tendency to force sink or swim results. Between 2008 and 2017, the total number of newsroom employees declined 23%.Though technology does create a demand for new jobs, so far, it has not been enough to offset the loss. The number of digital employees increased by 79%, but that only created around 6000 new jobs while there were 32,000 layoffs within the same time frame. It is important to note that these numbers could change within the coming years as the industry finds new ways to adapt.

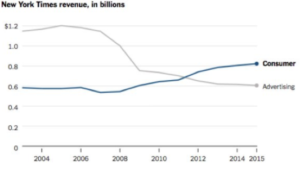

One way the industry has started to adapt is by shifting away from using advertisements as its main source of its revenue. Big players like the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and the Chicago Tribune grew their digital subscriptions in 2016 by 46%, 23%, and 76%, respectively. While top performers have been able to keep their heads well above water, both digital and print circulation for the industry as a whole saw an 8% decline in that same year. Getting subscribers is not easy for a majority of newspapers with less of a cult following. People tend to trust far-reaching, big publications like the NYT, thus keeping the high-circulation outlets right at the top.

The other way to get subscribers is by targeting a specific readership. In a 2017 study by the American Press Institute, the top reason cited by subscribers who were willing to pay for news services was that the outlet offered unique content on topics they personally cared about. Thus, if you do not have the clout of having the highest circulation in the country, differentiating your content could be the way to go.

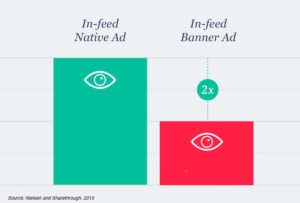

Differentiating content does increase the likelihood of attracting a higher subscription rate, but it also has another crucial bonus—it appeals to advertisers. Sites like Buzzfeed and Refinery 29 have already employed a tactic known as “native advertising.” These sites target a specific audience and integrate advertising into their content, making the product placement relatively subtle and extremely valuable. Disney could pay for a pop-up ad that people click out of immediately, or they could instead pay Buzzfeed to create a quiz called “Eat Your Way Through Disney Parks And We’ll Guess How Old You Are.” Studies have shown that consumers find native advertising is more interesting, informative, and useful than traditional ads. Though Buzzfeed and Refinery 29 do not charge for subscriptions, the money they make in sponsored content keeps advertisers happy and their profit margins high.

Another way the newspaper industry is fighting back is by playing Facebook and Google’s game of controlling consumer data. Industry executives are well aware that advertisers are willing to pay high amounts for accurate and verified data about potential consumers who visit their sites. Several publications have started doing this by joining coalitions aligned with advertising technology providers, whose goal is to leverage audience data. One example is the Local Media Consortium, who says they are “focused on increasing member companies’ potential share of digital revenue and audience by pursuing new relationships with a variety of technology companies and service providers.” For newspapers, joining this kind of group instead of letting a third-party interfere can help put their profit margins back on track.

The dust of the industrial revolution has not fully settled, but there seems to be a path forward for news publishers. Though big names like the New York Times seem to be the ones most likely to forge ahead unscathed, smaller-scale publications still have a chance to succeed. Right now, newspaper companies may be discouraged and might blame technology for shrinking their profits. But this is just an example of technology doing what it does best: forcing progress. The internet has allowed billions of people to access news across the globe, connecting people to information like never before. The journalism industry just needs to catch up. And it will.