As the economic crisis in Turkey hit emerging markets in the last few months, the Indian currency dropped to an all-time low against the dollar. At present, $1 is equivalent to nearly 72 INR. Five years ago, a report by Morgan Stanley, placed India in a club dubbed the “Fragile Five” – the emerging markets most vulnerable to ripple effects and external shocks. Although the country’s economy is perhaps not as fragile at present, the rupee’s fall shows that it is still vulnerable in many ways.

One of the major reasons for the fall is the incessant outflow of dollarsfrom the Indian market, which in turn was caused by the hike in interest rates by the United States Federal Reserve. The rate hikes make dollar assets more appealing to investors than the Indian market whose “emerging” status also means that it is more risky.

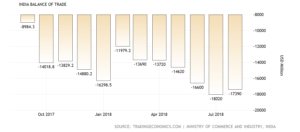

Moreover, India is extremely dependent on imports from other countries, especially when it comes to oil. According to The World Factbook published by the Central Intelligence Agency, India is the third largest importer of crude oil in the world. A steady devaluation of the rupee against the dollar would result in greater cost for India to buy fuel.

President Trump’s embargo on Iran also does not help matters. India is among the biggest buyers of Iranian oil, second only to China. With Washington adopting a tough stance, Indian refiners have already decided to reduce their crude oil imports for the next month.

All sectors will be affected because India’s economy is heavily dependent on fossil fuels and it is likely that the oil industry will transfer their cost over-runs to consumers. The devaluation of the rupee will also have an impact on the cost of other imports, making it harder to control inflation.

While the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), the central bank which controls the country’s monetary policy, has steadied the decline in value of the rupee, so far it has done nothing to stop it. The RBI’s last few efforts at intervening have not really helped the Indian economy and some commentators say that this time around the RBI should do nothing. This is perhaps because a devaluation of currency also has a few advantages – like short-term domestic growth.

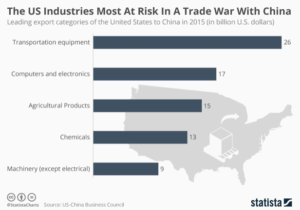

For starters, with increase in the prices of imported goods, consumers are more likely to switch to products made in the country, giving a much-needed boost to the domestic sector. This in turn might have an effect on the Chinese economy – China is India’s biggest trading partner with the latter’s trade deficit to China reaching a staggering $51 billion.

Exports also tend to benefit from a falling exchange rate. A relatively stronger foreign currency will have more purchasing power to buy products made in India, boosting the low growth in exports in recent years. Many Indian exporters believe that this devaluation will not only help India compete with Chinese products abroad but also open up the Chinese market itself.